August 6, 2018

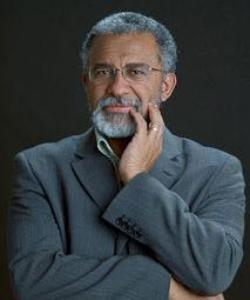

This blog features Dr. Johann Buis, professor of Music History in the Conservatory of Music as he discusses his passion for teaching students about opera literature and music of the African Diaspora through the lens of his unique personal journey.

Associate Professor of Music, Dr. Johann Buis, lauds opera as the “all-inclusive” art form. Productions can cost as much as 50 million dollars, yet it is well spent, encompassing theater, stagecraft, music, world literature, ancient mythology, and history. However, opera’s richness and dynamism was denied to Dr. Buis during the most formative years of his life.

Associate Professor of Music, Dr. Johann Buis, lauds opera as the “all-inclusive” art form. Productions can cost as much as 50 million dollars, yet it is well spent, encompassing theater, stagecraft, music, world literature, ancient mythology, and history. However, opera’s richness and dynamism was denied to Dr. Buis during the most formative years of his life.

Buis grew up in South Africa, in the midst of apartheid. The government forced his family to relocate twice, and 146 laws prevented him, as well as others of his skin color, from access to political, cultural, and economic practices. One of these practices was opera. He could not attend the performances, not even when a new opera house, a shining beacon of the craft, was built in his hometown. However, this did not stop him from developing a love and appreciation of opera that he still has today. Dr. Buis recalls his young self as a “fanatical listener to the radio,” which showcased an opera program Sunday nights. Each week he would feed his craving for the music; his father, a musician, would further facilitate Buis’ self-education with opera scores and a collection of opera records. Dr. Johann Buis professes that it is clear that opera had a power that went far beyond the four walls of the theaters that were denied to him. Being deprived of his favorite music, young Buis found himself making every effort he could to combat his forced deprivation.

Now, Dr. Buis wants to impart his love and appreciation of opera on the generations passing through Wheaton College’s Conservatory of Music. Each even year, he teaches two courses, the first of which is his Opera Literature course.

Opera is wrongfully stereotyped, Dr. Buis adamantly believes. Commonly conceived as an old, stuffy craft properly left to even older, stuffier people, opera was actually born mistakenly from the excited enthusiasm of revolution. With the advent of the printing press in the seventeenth century, Western Europe was swept up in a flurry of paper and ink, printing everything and anything they could. Some of the most prominent works reproduced were ancient Greek texts. First printed in Italian, the language of the streets, these texts confused their readers with words like “chorós.” They realized it must mean “chorus.” This revelation provoked another series of revelations. Dr. Buis excitedly narrates the Italians’ thought process: “What is this word, “chóros”? It must mean “choir!” Wait, if there was a choir, were they the only ones who sang, and everyone spoke normally? Ohhh no, everyone sang! Can we do that? Yeah! Let’s do that!” This revolutionary realization prompted a group of Italian men, one of whom was Galileo’s father, to start a trend that would grow and flourish to become what we know today as opera.

Opera should not be considered a bunch of men and women singing in artificial voices, peacocking about a stage. Rather, Dr. Buis says it should be appreciated because “you will never find such a total work of art in one place: theater, acting, stage craft, painting, visual arts, aesthetic arts, dynamics, acting, sword fighting…” The list goes on and on.

Through this all-inclusive craft, one discovers something vital about human nature: the human condition. Vice. The battle of good against evil. Opera is rife with this theme. Everyone loves it when good overcomes evil, but many times the good man is the one who died. This, Dr. Buis reveals, is a common plot line that comes from Christ: “This is the very point in which we understand that opera is a reflection of the human condition. It points us to something bigger than that: the human desire of the greater good, for common fair play, for that idea of goodness triumphing over evil, because here you see the ultimate goodness triumphing over evil: Christ.”

During his class, Buis insists that every single student attend the opera. Just a twenty dollar ticket and a train ride away, students have access to world-class opera at the resplendent Lyric Opera House in Chicago. This, Dr. Buis exclaims, “is the best birthday gift, the perfect date, and the best exposure for friends” because “you enter this sumptuous opera house and realize this music has a power all of its own… you just need to present yourself and the music will take over.”

Opera is grounded in Western European tradition, but it has become universalized. Even at the start, opera took its audience to far off lands or even other worlds. “The idea of exoticism, the exotic other, that which is unfamiliar to us… is at the heat of opera,” Dr. Buis imparts.

These ideas of exposure to the unfamiliar, as well as breaking down stereotypes about the world are formative to Dr. Buis’ second course unique to this fall semester: The Music of the African Diaspora.

In this class, Dr. Buis wants his students to affirm their ancestral musical practices if they are of African descent, or increase their knowledge, respect, and love of music outside their ancestry. This exposure to the unknown, as early opera was so fascinated with, is something that Dr. Buis believes needs to be emphasized on campus. He says, “[Wheaton College] is, by its very profile, fairly strong in the dominant culture, and people who come of the African descent, or people who embrace the love for African culture are always at the margins. They never seem as significant in their pursuit on campus, or their academic pursuit.”

Dr. Buis sees his class as an opportunity to challenge students to expand their horizons, and make a culture, which if not their own, seem personally relevant and infinitely valuable. Buis wishes, only half-jokingly, that they could advertise his course as, “Ever thinking about Africa in your future? Take this course!” It goes far beyond looking solely at music. Humanitarian and goodwill ambassadors go to Africa thinking that because they share a common language, such as English or French, they know the people. What they fail to realize is that below the surface, there is a vast array of cultural practices that are divergent from what the dominant western culture, French or English, presents.

These people, spread between two cultures possess a unique ability to move between them, whereas people conversant only in their own dominant culture practice have difficulty finding connection and respect in and for other cultures. Dr. Buis believes the exposure within his course helps students learn to bridge this gap. It also connects people who have different backgrounds in a trans-cultural exploration and learning experience. Unique cultural patterns, behavior, emotions, and practices are expressed and integrated in music. He says, “They will not only learn the remarkable difference of people who came throughout the world from Africa, but also they will understand their own culture with far greater depth.”

Two courses, Opera Literature and Music of the African Diaspora, seem as different as they can be. But, they are intertwined in the passion, life experience, and connections of one professor, Dr. Johann Buis, who wishes to use them to inspire the same appreciation, respect, and passion that he has in the hearts of Wheaton College students.