The Credit For My Life is God's Grace

How the generosity of God’s people helped Ukrainian war refugee George Shoning ’62 find a home at Wheaton College.

In the fall of 1943, George (Schudnachowski) Shoning ’62 became one of the youngest refugees to flee the Russian town of Voladarsk Volinskyy in what is now modern-day Ukraine.

Of German and East Prussian ancestry, George’s parents, Anna and Paul Schudnachowski, had suffered greatly under Stalin’s rule. Within a year of George’s birth, his grandfather, great uncle, and uncle were accused of anti-Communist sentiment, arrested, and executed.

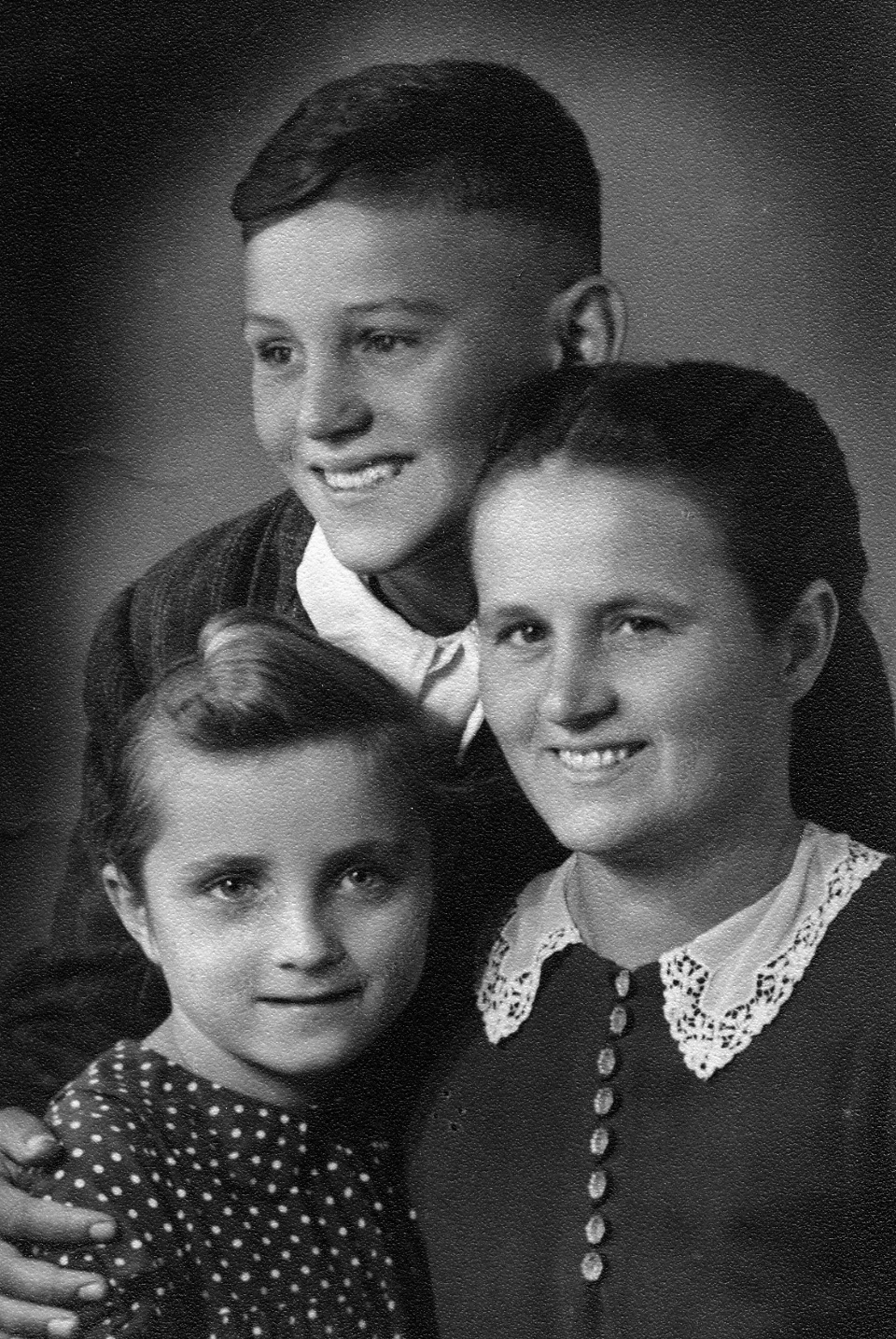

In fear for their lives, George’s parents packed a horse-drawn wagon with six-year-old George and his nine-year-old sister Adelle Shoning Ransom ’66 to seek safety in German-occupied Poland. They were joined by George’s Aunt Alwine and her four children.

The German authorities assigned the family a house that had belonged to a Polish family evicted by the Germans. They lived there for nearly two years.

But as the Russians continued to force the retreat of German forces, the Schudnachowskis joined with other families fleeing Germany on foot with their possessions in wagons. But the Russians overtook them on the road, confiscated their belongings, and rounded up George’s father Paul along with the other men in the convoy.

Paul asked to be allowed to pray with his family one last time. Hugging Adelle, he knelt on the ground and prayed, “My God, whatever way you lead me, I will not complain if you protect my wife and my children from harm.”

Sadly, Anna went to her grave without ever learning the fate of her husband. It was not until many decades later that, after a chance encounter in Ukraine, George came to learn the details of his father’s life and death.

A Mother’s Courage

Having just lost her husband, George’s mother Anna and his Aunt Alwine led the six children through the cold February night on foot, because the Russians had confiscated their wagons. Their clothes were too thin to protect them from the cold, so they sought shelter in a farmhouse.

In the farmhouse, they were dismayed to discover Russian soldiers bedded down in the straw. One soldier, however, rose and made room for the family. Fortunately, after a sleepless, prayer-filled night, they left unharmed, and they eventually found their way back home.

They finally returned to their old home, until a few days later, they were forced to move out when the home’s former occupants returned from eastern Poland.

The only shelter they could find was a burned-out farmhouse whose stalls were filled with dead animals. But the frigid temperatures kept the burned flesh and the potato harvest frozen, sustaining the family for several months until the women found jobs.

“Every morning, they would gather us children, and we’d kneel, and everyone prayed for God’s protection and for food,” says George.

After WWII ended in May 1945, the family was sent to a refugee camp in East Germany. For two years, they struggled to survive by begging for food from farmers in neighboring communities.

Then, one day, Russian authorities told Anna and Alvine that a truck was coming to pick up the family and return them to their home in Voladarsk Volinskyy. Rightfully suspecting that the Russians would actually deport the families to Siberia, Anna negotiated for the truck to come the following morning.

That night, Anna, Alwine, and their children fled for their lives. For two harrowing hours, George, his mother, sister, and one of Alwine’s children crept past armed guards on the East/West German border. Alwine and the rest of her children escaped to the British Zone a few days later, traveling by a different route to avoid suspicion.

They crossed at a coal mine near Schöningen, where today, a memorial cross stands in honor of the 26 people who died between 1945-1951 while attempting to escape.

Years later, George and his sister Adelle changed their name from Schudnachowski to Shoning to mark the miracle that occurred at Schoningen.

Once in the British Zone, Anna and her children were assigned to live in one room of a farmhouse owned by a German farmer. Anna worked in the farmer’s fields, and the children went to a local school. Alwine and her four children were assigned to live in a different farmhouse a short distance away.

In 1949, a traveling preacher inspired George to dedicate his life to Christ. To this day, he has the small German New Testament containing his signed commitment and the life verse chosen by the preacher, 2 Corinthians 5:15: “And he died for all, that those who live should no longer live for themselves, but for him who died for them and was raised again” (NIV).

Coming to America—and Wheaton College

In October 1951, George, Anna, and Adelle arrived in Arlington, Massachusetts—sponsored by the First Baptist Church of Arlington, which participated in the Church World Service program to help WWII refugees resettle in the United States. George and Adelle learned English quickly and excelled at school.

While preparing for college during his senior year of high school, George consulted with a friend from Tremont Temple Baptist Church, longtime Wheaton College trustee Dr. E. Joseph Evans.

George longed for a school that would complement his intended mathematics concentration with classes in the social sciences, literature, philosophy, theology, and the arts.

“Uncle Joe” steered George to Wheaton College and put him in touch with Susan Howes, who, with her husband, established a trust fund to help needy students. Mrs. Howes agreed to fully fund both George’s and Adelle’s four years at Wheaton College. George majored in mathematics and took as many liberal arts courses as possible, scoring classes with Wheaton legends Dr. Arthur Holmes ’50, M.A. ’52, Dr. Beatrice Batson, M.A. ’47, and Dr. Alton M. Cronk.

He taught Sunday school at a YMCA on Chicago’s south side, served as the main photographer for the Tower, and played soccer under coach Dr. Robert C. Baptista ’44.

A member of ROTC, George was named a “Distinguished Military Graduate” and commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Artillery Branch. He went on to serve for three years at a U.S. Army Detachment supporting a German Air Defense battalion in Frankfurt, receiving a Certificate of Achievement from the U.S. Army Europe “for exceptionally meritorious service.”

“I felt I needed somehow to repay the country because of how it provided for me and my family,” he says.

Life Comes Full Circle

George and his wife Allida make their home in Boulder, Colorado, where they both worked for IBM and have since retired. They have two children, Paul and Alexa, and four grandchildren.

In 2003, George and Allida traveled to Ukraine, assisted by a retired Baptist minister who organized genealogical tours.

While ambling through the village where his father grew up, they met two elderly women. One mentioned that a Schudnachowski owned a house nearby. While following a dirt road toward the house, George and Allida encountered a middle-aged couple walking barefoot with shoes in hand. The Shoning’s driver asked if the house ahead belonged to a Schudnachowski.

“Yes, I am Valentin Schudnachowski,” the man replied.

George leaped from the minivan and, after a few more questions, confirmed that Valentin was his first cousin, the son of his father’s youngest brother.

From this long-lost cousin, George received the first news he had ever had of his father since the day his father had been arrested by the Russian Army in 1945.

His father had been sent to a labor camp in northern Siberia, where prisoners suffered from terrible conditions. At one point, his father had become so ill and emaciated from typhus that he had been mistaken for dead, and his body was tossed onto a pile of corpses.

Remarkably, a passing female camp worker detected that he was still breathing and nursed him back to health.

In 1947, after serving two years of his sentence, George’s father was released on probation. He arrived in the Siberian city of Irkutsk near starvation, wearing a thin cotton jacket and no gloves in -40 degrees Celcius with the stipulation that he could not communicate with the outside world for the period of probation. The people of the local Baptist Church took him in and cared for him.

Paul’s wife related the story of his life as a prisoner when George and Allida visited Irkutsk in 2004. After his years-long search for his family had provided no leads, Paul eventually remarried. Sadly, he died in 2001—only two years before George’s visit to Ukraine.

“Had we come an hour later, or another day, I would not have met my cousin,” says George. “I always think, ‘why me?’ There were thousands of devout Christians who were killed and suffered. I think my mother’s prayers were part of it. I am extremely grateful to God and his people who, out of love for Christ, helped us.”

“The credit for my life is God’s grace. My family and I received so much undeserved love from God’s people that no matter how much gratitude we express, it never can be enough.”

Invest in Tomorrow's Changemakers

Sadly, the world today faces many of the same crises as it did when the Shonings fled Europe, including the greatest forced migration crisis since World War II. Together, we are called to shine the light of Jesus Christ to a world desperately in need of his love.

Your gift to the Wheaton Fund helps train servant leaders to share the saving love of Jesus Christ with a fallen world. Your support also keeps Wheaton as affordable as possible to students like George Shoning, who enrich the Wheaton community with a diverse spectrum of talents, experiences, and backgrounds.