Augustine in Art

To See a Saint: Exploring Augustine in Art

Jerusha Crone '19

Often throughout art history, Saint Augustine appears in images as an exemplar of spiritual and academic excellence. With our own wealth of such exemplars at Wheaton College, maybe we stand to gain from an expanded view of the saint. What if the Saint Augustine we need to see is Augustine the pear thief? Maybe we need the Augustine who admits so earnestly he understands neither his own nature nor that of God. Perhaps we can learn from the Augustine fighting to establish doctrinal soundness in an age of rising and falling ecclesial power. Regardless of the particular need, artistic portrayals of the saint may give us just such opportunities to see him anew.

At times there can seem to be a dissonance between the Augustine we encounter in Confessions and the Augustine we see portrayed in art. Augustine in the Confessions is an at times timid, at times tenacious saint whose honest questioning, unceasing praise, and ongoing existential crisis color his dynamic conversation with God. Each word points us to a particular man’s particular mind; the miracle of literature resurrects that mind to speak to us as if present here today. In comparison, the Augustine found in images throughout art history often seems distant. Yet this distance is not merely valid, but valuable. As images of Augustine rose to popularity centuries after his death, they drew upon not only his life, but also legend and legacy. Therefore, the images are not portraits that tell us what he looked like. Rather, Augustine is used as a symbol. He represents different ideals and ideas prominent in the context of each work in which he is found. When we encounter Augustine in art, we encounter visual interpretations of his ideological significance.

What is of interest, then, is how Saint Augustine has been visually interpreted in different times and places. Thus, we ask these kinds of questions as we explore portrayals of Augustine: What did Augustine mean to the makers of this image? How does this image ask me to see Augustine? Emerging from its own context and purpose, each work has its own particularity in its interpretation of the saint that is worth considering. And this year, as the Wheaton community reads Sarah Ruden’s translation of Confessions, we have the privilege of reinterpreting Augustine’s story for our own time, with our own particularities, in light of the gospel which spans all contexts—with images to help us on our way.

The faithful scholar: The Life of Saint Augustine by Benozzo Gozzoli

The Life of Saint Augustine by Benozzo Gozzoli includes seventeen frescoes depicting the saint’s life from the beginning of his education to his death. This cycle was commissioned circa 1464 for Sant’Agostino in San Gimignano by Fra Domenico, an Augustinian friar appointed to reform the monastery. Fra Domenico, a doctor of Sacred Theology, hoped to re-instill in his monks the pursuit of faithful scholarship so exemplified by Saint Augustine. Thus, Gozzoli’s frescoes seek to emulate this same spirit: rigorous learning united with faith.

In Augustine Brought to the Grammar Master (fig. 1) we see the young saint delivered into the hands of stoic schoolmasters by his mother Monica. The composition is colorful and playful, resounding with the schoolboyish folly Augustine mourns in Confessions. In Augustine Reading Rhetoric in Rome (fig. 2), the color pallet dulls and the composition tames into perfect one point perspective. Augustine is shown with eyes downcast and a vacant expression as he matures into worldly wisdom. The frescoes culminate above the altar with Tolle, Lege (fig. 3) and Baptism of Augustine (fig. 4). These scenes are simpler than those prior, and they resonate with a peace and order as faith and learning culminate in both personal conversion and public sacrament.

Augustine's intellectual pursuits then continue. Following frescoes depict him establishing his monastic order, encountering the boy with the seashell trying to empty the ocean (fig. 5), being appointed Bishop, fighting heretics, and having a vision of St. Jerome in his study. The final scene, The Funeral of Augustine (fig. 6), takes the saint’s life of learning and directly connects it to the monastery. It portrays the funeral attendees in the habits of the Augustinian Friars, who are understood to carry on his legacy. Gozzoli’s Augustine is meant to lead the monks towards deep devotion in both faith and learning.[1]

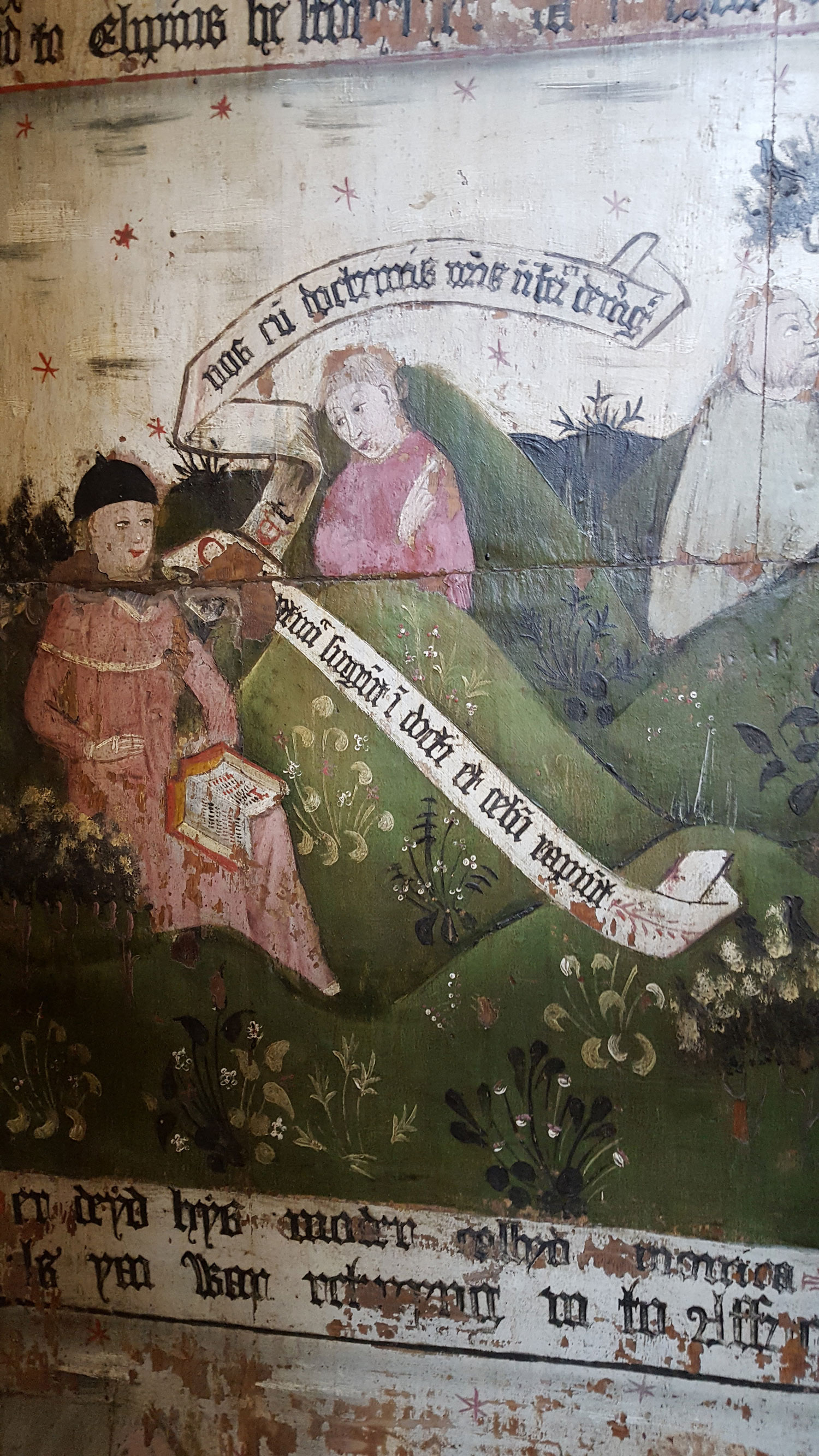

The ordinary saint: The Augustine Screen in Carlisle Cathedral

The Augustine Screen in Carlisle Cathedral, while depicting many of the same scenes from Augustine’s life, portrays a simpler, humbler Augustine. The paintings, meant to be seen by local congregants, present the story of the saint’s life in a straightforward, comic book-like style with captions below each scene. The failures of learning and prestige rise to prominence throughout the work. Scene 6 (fig. 7) highlights a conversation where Augustine, upon hearing the story of Saint Anthony cries, “The ignorant rise up and take heaven by storm and we with our learning are being thrust down to hell?” We see Ambrose preaching against the letter of the law and Augustine’s reluctance as he is ordained. A whole painting is dedicated to a toothache of the saint briefly mentioned in Book 9 of Confessions (fig. 8). Humility and relatability are emphasized again and again. The Augustine depicted here is popularized and simplified for mass consumption, pun intended. He is an icon of ordinariness, encountering a Gospel just as applicable for the housewife or craftsman in the congregation as for the scholar or priest. [2]

The emotion-filled human: Conversion of St. Augustine by Fra Angelico

Fra Angelico’s 1430 Conversion of Saint Augustine (fig. 9), though relatively undiscussed, is among the more recognizable paintings of the saint. Famed art historian Vasari categorized Fra Angelico as primarily a Dominican friar who painted for God, not a painter, thus over spiritualizing his work and leaving Angelico out of many serious discussions about quattrocento painting and culture.[3] It’s not terribly difficult to see why he would be isolated from other Renaissance painters. The Conversion of Saint Augustine fails to align in typical one point perspective. The scale of the figures is off. The vibrant flatness of Angelico’s work likens it more to late Gothic, even Byzantine art than that of the Renaissance.

Yet Fra Angelico was not uninfluenced by his surrounding culture. His work emulates both popular humanism and neoplatonic theology. His Augustine, folded over with hands on his face, is among the most tender and realistic found in images of the saint. The conversion here is not a stagnant scene. It has neither lifelike realism nor stiff stylization. It rests in a middle ground. The overcome Augustine, though haloed, can be said to be nothing more than a real human experiencing real emotion, yet the space he inhabits borders on abstraction. The scenery acts more as a place where meaning can ruminate and swell than as a literal garden.[4] The abstraction invites contemplation. Overall, the painting doesn’t as much present a turning point in Augustine’s life as disassemble the scene into a meditation on a moment—a moment of overwhelming grace.

The philosophical theologian: Florence, Laurenziana. Plut. 12, Cod.17

An illuminated manuscript of Augustine’s City of God (fig. 10) from 1120 highlights Augustine’s role as mediator between Neoplatonist philosophy and Christianity. The manuscript belonged to Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici whose Father, Cosimo il Vecchio, began the Platonic Academy at Florence. Augustine is portrayed oversized, flanked by smaller monks. He and the monks all gaze intently across the page at the neighboring scene (of which unfortunately no image has been provided) where philosophers in academic regalia return the gaze. This compositional tension alludes to the debate over the nature of the human body and the soul. Augustine defends the possibility of a redeemed body in heaven while the Platonists would have argued for a soul one day released from physical form. Above the two miniatures hover two more scenes depicting saints in heavenly glory and the judgment of souls. The philosophical debate below is therefore presented as one of eternal significance. Augustine here represents the hope of a body restored, but also the impending judgment of the soul for both philosopher and theologian reading the text.[5]

The monastic bishop: Various altarpieces

Augustine is portrayed as bishop in countless works too numerous to explore in great detail. In such images he is often presented alongside other saints and his characteristics are simplified for easy identification. Luca Signorelli painted Augustine in the company of Athanasius and Archangels in the bottom left corner of Virgin and Child with the Trinity (fig. 11). The work was commissioned in 1513 by the confraternity of the Holy Trinity, and Augustine’s inclusion is due to his famed devotion to trinitarian doctrine.[6] In Michael Pacher’s Altarpiece of the Church Fathers (fig. 12) from 1482 Augustine, cloaked in black, gestures towards a child at his feet. The child can worthily be assumed to be the one whose attempts to empty the ocean Augustine found so convicting in regards to the absurdity of his own attempts to understand the nature of God.[7] Giotto’s Vault of the Doctors of the Church (fig. 13) from the late 13th century includes Augustine, Gregory the Great, Jerome, and Ambrose, all swirling on a dazzlingly colorful ceiling in The Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi. In the bottom register, Augustine sits and instructs a monk, highlighting his establishment of his monastic order.

The classical academic: Saint Augustine in His Study by Vittore Carpaccio

Carpaccio’s Saint Augustine in His Study (fig. 14) from 1502 is the last of three paintings dedicated to Saint Jerome in the Scuola di San Girolamo in Venice. The work portrays the apocryphal story of Saint Augustine’s vision of Saint Jerome. While contemplating the glory of heaven, Augustine is interrupted by the voice of Jerome who warns him against attempting to use his human mind to comprehend heavenly mysteries. Fittingly, Augustine himself is depicted as the ideal Renaissance scholar. The work does not simply negate the worth of the human mind, however. While human attempts to understand glory are unsuccessful, glory shines through into human reality and culture. Carpaccio elegantly intertwines humanism and humility.

Symbolic objects are scattered throughout the study. Augustine is surrounded by papers, books, and musical scores. Behind him stands an altar filled with liturgical objects, a statue of Christ, and a Bishop’s staff. More secular objects such as medals, vases, and a nude statue decorate the adjacent wall. Research suggests Augustine here is meant to represent Bessarion, an accomplished Cardinal and classic Renaissance man, whose interests ranged from astronomy to classical literature, all represented in the painting. Bessarion or not, this Augustine is distinctly human and surrounded by symbols of the best of human achievement.

The only unusual element in the harmonious composition is the lighting. Though natural in appearance, it has an unidentifiable source. The source of light is of course none other than St. Jerome’s presence. The subtlety of the miracle here is powerful. In true Carpaccio fashion, the scene at first glance appears to be just a scene in everyday life. Yet, here the supernatural infuses the moment without compromising naturalism. Augustine’s human quest for wisdom, though limited, is nonetheless divinely illuminated.[8]

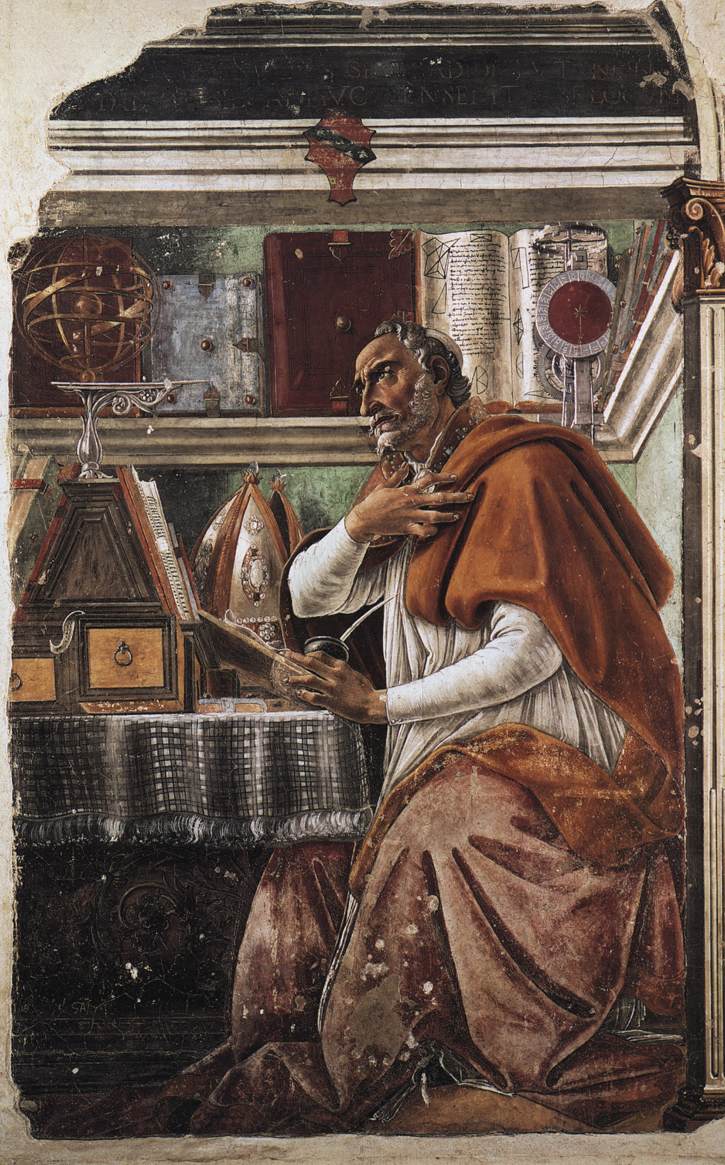

The divinely interrupted student: Saint Augustine in His Study by Sandro Botticelli

Botticelli also depicted the vision of St. Jerome in his own Saint Augustine in His Study (fig. 15) in 1480. Again, we see detailed and metaphorical still life objects behind Augustine. The mystical quality of the light is further emphasized by an inclusion of a clock that explicitly marks the hour as sunset, despite the midday glow throughout the room. In contrast to Carpaccio’s work, however, the moment is much more dramatic. Augustine here is caught in between scholarly thought and amazement at the vision. His hand is thrust to his heart. His gaze appears abrupt, just raised from his work. Unlike Carpaccio’s steady reality, this scene emphasizes a sudden interruption by the divine into the everyday. The painting was commissioned for Umiliati monks who around this time began transitioning from their previously accepted labor based living to accepting the more studious Rule of St. Benedict. Thus, it emphasizes a transition of focus, guided by God. [9]

The monk at peace: Saint Augustine in His Cell by Sandro Botticelli

Fourteen years later, Botticelli would revisit the saint once again, painting Saint Augustine in His Cell (fig. 16).[10] This work, commissioned by a convent of Augustinian Hermits, portrays Augustine in bishop’s clothing, yet inhabiting a simple monk’s cell. His face is peaceful as he looks down at his writing, unlike the empty downcast expression seen at San Gimignano. The space he inhabits is almost stagelike, emphasized by the curtain behind him. The cell is undistracting, allowing all attention to fall on the working Augustine. The work resonates with a calm humility. This is a scene of true rest. And fittingly so, for in the words of Saint Augustine—words that we will doubtless be reminded of many times this year, though perhaps not often enough for our anxious, tired, and burdened hearts—“In yourself you rouse us, giving us delight in glorifying you, because you made us with yourself as our goal, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.”

---

[1] Cole Ahl, Diane. “Benozzo Gozzoli: The Life of Saint Augustine in San Gimignano” in Augustine in Iconography: History and Legend. Edited by Joseph C. Schnaubelt, OSA and Frederick Van Fleteren. (New York: Peter Lang. 2003) 359-382.

[2] Colledge, Edmund. “The Augustine Screen in Carlisle Cathedral” in Augustine in Iconography: History and Legend. Edited by Joseph C. Schnaubelt, OSA and Frederick Van Fleteren. (New York: Peter Lang. 2003.) 383-430.

[3] Spike, John T. Fra Angelico. (New York: Abbeville Press. 1996.) 60.

[4] Didi-Huberman, Georges. Fra Angelico: Dissemblance and Figuration. trans.Jane Marie-Todd. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1995). 18.

[5] Steinhauser, Kenneth B. “Augustin Moralisé: Some Observations on Florence Laurenziana, Plut. 12, Cod. 17.” in Augustine in Iconography: History and Legend. Edited by Joseph C. Schnaubelt, OSA and Frederick Van Fleteren. (New York: Peter Lang. 2003.) 577-593.

[6] Henry, Tom and Lawrence Kanter. Luca Signorelli: The Complete Paintings. (New York: Rizzoli International Publications. 2002.) 232.

[7] Evans, Mark. “Appropriation and Application: The Significance of the sources of Michael Pacher’s altarpieces.” in The Altarpiece in the Renaissance. Edited by Peter Humfrey and Martin Kemp. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1990.) 106-128.

[8] Fortini Brow, Patricia. “Carpaccio’s St. Augustine in His Study: a Portrait Within a Portrait” in Augustine in Iconography: History and Legend. Edited by Joseph C. Schnaubelt, OSA and Frederick Van Fleteren. (New York: Peter Lang. 2003.) 507-547.

[9] Lightbown, Riger. Botticelli: Life and Work.(Los Angeles: University of California Press. 1978) 49-51.

[10] Ibid., 119-121.

Figure 1 - Augustine Brought to the Grammar Master, from the Fresco cycle of St. Augustine in Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano (1464-65), Benozzo Gozzoli

Figure 2 - Augustine Reading Rhetoric in Rome, from the Fresco cycle of St. Augustine in Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano (1464-65), Benozzo Gozzoli

Figure 3 - Tolle, Lege, from the Fresco cycle of St. Augustine in Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano (1464-65), Benozzo Gozzoli

Figure 4 - Baptism of Augustine, from the Fresco cycle of St. Augustine in Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano (1464-65), Benozzo Gozzoli

Figure 5 - The Parable of the Holy Trinity, from the Fresco cycle of St. Augustine in Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano (1464-65), Benozzo Gozzoli

Figure 6 - The Funeral of St. Augustine, from the Fresco cycle of St. Augustine in Apsidal chapel, Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano (1464-65), Benozzo Gozzoli

Figure 7 - Scene 6 of The Augustine Screen in Carlisle Cathedral, Carlisle, Cumbria

Figure 8 - Scene 9 of The Augustine Screen in Carlisle Cathedral, Carlisle, Cumbria

Figure 9 - Conversion of Saint Augustine, Fra Angelico, 1430

Figure 10 - Florence, Laurenziana, Plut. 12, Cod. 17, from an illuminated manuscript of Augustine's City of God from 1120

Figure 11 - Virgin and Child with the Trinity, Luca Signorelli, 1510

Figure 12 - Altarpiece of the Church Fathers, Michael Pacher, 1482

Figure 13 - Vault of the Doctors of the Church, Giotto di Bondone, late 13th century

Figure 14 - Saint Augustine in his Study, Vittore Carpaccio, 1502

Figure 15 - Saint Augustine in his Study, Sandro Botticelli, 1480

Figure 16 - Saint Augustine in his Cell, Sandro Botticelli, 1490