A Century of Commitment, Community, and Christ at the Center

Explored through the eyes of a fourth-generation student and her great-grandparents, the Wheaton of 1921 is vastly different from the Wheaton of 2021. Still, the most important things remain the same.

Words: Katherine Braden ’16

Photos: Buswell Library Special Collections and

the Family of Kathleen Sears Sawyer ’21

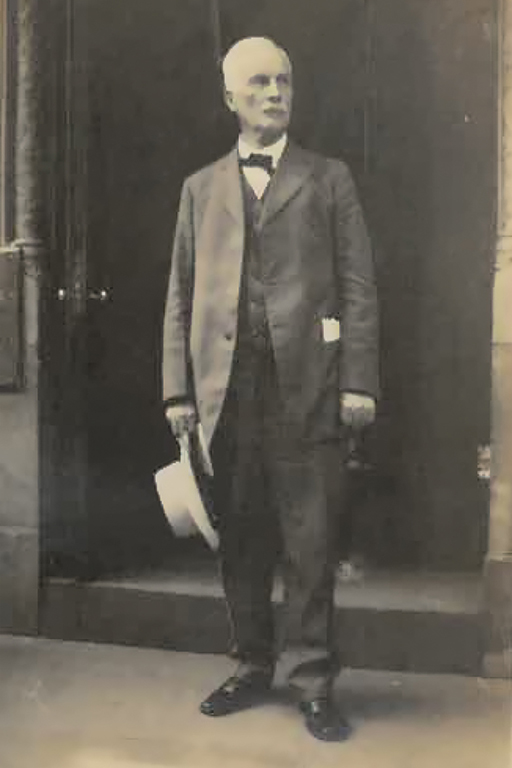

President Charles Blanchard

c. 1921

A century ago, 729 W. Irving Avenue was a large, red brick house on a three-acre farm. The farm—with its chickens, gardens, and orchards—belonged to the Sears family. It was there that Kathleen Sears Sawyer 1921 lived while attending Wheaton College. And it was there, at 729 W. Irving Avenue, that she met her husband, John Sawyer 1921.

Now, Allie Schraeder ’21, John and Kathleen’s great- granddaughter, often walks by 729 W. Irving Avenue. The red brick house has been demolished, and in its place stands the Hollatz House Duplex, campus housing for 12 students. In place of the Sears’ gardens are tennis courts.

“It’s surreal to be in the same place my ancestors walked, slept, studied, and ate,” said Allie, a fourth-generation Wheaton student. “There’s something about Wheaton that people keep coming back to.”

She’s right. Wheaton has myriad legacy families, some spanning seven generations. Allie will graduate exactly a century after her great-grandparents, and though many physical spaces remain the same, her experience of campus is markedly different.

In 1921, Blanchard Hall, Wheaton’s iconic building, had stood proudly atop its hill for 68 years. Also in that year, Charles Blanchard, Wheaton’s second president and son of founder Jonathan Blanchard, led the student body of 300. The Sawyers attended most of their classes in the “Main Building,” as it was called, and they were also summoned to chapel by the sound of the chiming tower bell.

Like most students, John rented a room at a private residence nearby—he stayed in the home of Trumble Howard, who was the grandfather of David ’49, M.A. ’52, Tom ’57, and Elizabeth Howard Elliot ’48. Kathleen visited friends in the women’s dorm, Williston Hall, nicknamed “The Red Castle,” with its luxury electric lights and steam heat, while John exercised in the state-of-the-art gymnasium—financed by and later named for Wheaton resident John Quincy Adams (a cousin of the second and sixth presidents of the United States)—with its indoor tracks and bowling alleys. The new Industrial Building, later known as Schell Hall, housed laboratories where the students attended classes on botany and zoology.

Engagement of Kathleen Sears 1921 and John Sawyer 1921

On Blanchard lawn sat the bright yellow, 16-foot domed observatory, known as the “Lemon.” The Sawyers may have used its 800-pound telescope to gaze at the stars. Perhaps they sat on the original concrete “Bench,” in front of Blanchard Hall, or sneaked away for some privacy in the long arborvitae hedge surrounding the campus, a favorite of courting couples.

Now, six presidents later, the Wheaton of 2021 boasts 2,400 undergraduates, 500 graduate students, and 75 campus-owned buildings. While the ratio of male to female students remains similar, present-day Wheaton sees a more equal balance of male to female professors. With the passing of the 19th amendment in 1920, one can only imagine how Wheaton’s female professors might have celebrated the historic moment. One of the main ways Wheaton has changed is in the racial and ethnic diversity of its student body. The Sawyers may have interacted with one or two students of color during their time at Wheaton. The Wheaton Allie attends is more racially and ethnically diverse, with one in four students identifying as a person of color. Initiatives like the Office of Multicultural Development, the Office of Intercultural Engagement, and the Shalom Community empower her to deepen her understanding of kingdom diversity.

Wheaton’s athletics have also expanded. In 1921, collegiate sports, still relatively new to Wheaton College, were only available to men. The three tennis clubs played on six courts where Pierce Chapel now stands. The Sawyers might have cheered on Wheaton men’s football, basketball, baseball, track, or cross-country teams. Students traveled by train to play against local teams like Loyola and the Chicago Y.M.C.A.

Now, Allie can cheer for Wheaton women and men, and she can also watch wrestling, golf, volleyball, softball, soccer, and swimming.

Adams Hall

Built in 1899, was first used as a gymnasium, once included a basement bowling alley for students, was used during World War II for one year as an army barracks, and, ever since a 2009 renovation, has housed the Department of Art.

Beyond sports, Wheaton’s focus on rigorous, Christ-centered academics and a strong liberal arts education remains a consistent theme. For both Jonathan and Charles Blanchard, intellectual training wasn’t the end; it was a means to an end—building up students’ solid Christian character in preparation for life-long service to Christ. Today, Wheaton academics echo that sentiment with the new Christ at the Core curriculum. Students can choose from over 40 majors while receiving a Christian liberal arts education designed to address 21st-century challenges.

Although they were limited to 12 majors, the Sawyers were required to take a variety of subjects—English, languages, and mathematics—and were allowed multiple electives. The flexible, diverse curriculum and biblically based classes prepared students to think and live well as servants of Christ in an emerging industrial society.

John, a Greek major, took courses in argumentation, Bible, and international law, as well as war aims and military drill. The latter two were a product of the Student Army Training Corps— an early version of the present-day Army Reserve Officers’ Training Corps—instituted to prepare college-going men for enlistment in World War I, if necessary. A Latin, mathematics, and music major, Kathleen was an accomplished pianist who accompanied Men’s Glee Club and the choir that sang during chapel. In the spring, she opened the windows of 729 W. Irving Avenue, and faculty and students gathered to hear her play Beethoven or Chopin. Now Allie, a voice and theater major, can practice jazz piano or prepare for her next opera in Wheaton’s new Armerding Center for Music and the Arts.

“Music and Wheaton are in my blood,” said Allie, who won the 2018 Wheaton Talent Show with an original comedic song, “Our Saga.”

Williston Hall

Although opportunities like Homecoming or Improv weren’t yet available to the Sawyers, they participated in other social activities. John was on the Student Government cabinet and worked for The Record. On Annual Campus Day, students had a day off from class and helped landscape the campus, stopping for a hot dog lunch. Students could also attend the Washington Banquet, now known as the President’s Ball, for a formal dinner.

“We can dance at that now,” laughed Allie. She stated a few more changes, like the addition of the Counseling Center and opportunities to study abroad. One crucial Wheaton principle hasn’t changed, though: intentional community.

In 1921, most Wheaton students belonged to one of six literary societies, or “Lits,” which were social groups more academically focused than Greek life. John was a member of the Beltionians, which attracted future preachers. Others included the Excelsiors, a favorite of the athletic men, the Aeolians for scholarly women, and the Boethallian Literary Society.

Though the “Lits” no longer exist, Allie found a similar Christian community among the members of Workout (Arena Theatre) and Concert Choir, as well as the women on her dorm floor. The focus on cultivating purposeful, God-honoring relationships among students and professors, and serving the surrounding community, is a highlight of her Wheaton experience.

Underlying it all is Wheaton’s commitment to Christ, which has remained firm through the decades.

The Sawyers’ classes and athletic events started with prayer and Scripture reading. They attended prayer meetings, daily chapel, and campus revivals. Christian social clubs and local, short-term mission trips were popular. Many classmates became missionaries. Inscribed into the cornerstone of Blanchard Hall, the campus motto, “For Christ and His Kingdom,” reminded them of their current and future focus.

“Students read Scriptures daily, prayed fervently, witnessed openly, and attended church regularly out of love and devotion to Christ and his Word,” said John Sawyer Jr. ’54, recalling his parents’ time at Wheaton.

The Wheaton of 1921 did not yet have a doctrinal statement, and it aligned basically with the fundamentalists of the day, a fact that was codified in 1924 when its first Statement of Faith was written. Today, the doctrinal statement, which is reaffirmed annually by Wheaton’s Board of Trustees, faculty, and staff, is a summary of biblical doctrine in the evangelical tradition.

“Wheaton has always aimed to do all for the glory of God,” Allie’s mother, Nancy Sawyer Schraeder ’85, said. “The commitment to Christ and his kingdom—to serving the Lord—that’s remained unchanged.”

Allie has seen her relationship with God mature at Wheaton. Though her summer plans to work at a comedy club in Chicago and attend Wheaton’s Arts in London program were upended due to the COVID-19 pandemic, she knows “God is using this time to build my character and make my faith stronger.”

Perhaps the Sawyers echoed Allie’s sentiment during Chicago’s deadly influenza pandemic in 1918, as they watched many of their fellow students fall ill and saw two classmates die. They also lived through a state-wide shutdown, and were ordered to isolate and wear face masks in public to stop the virus’s spread.

A century later, although much has changed since her great-grandparents attended Wheaton, Allie noted that the important things—academic excellence, a focus on community, and Christ at the core of life—remain the same.