A History of Technology at Wheaton College

Words: Melissa Schill Penney ’22

Photos: Tower Yearbooks and Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections

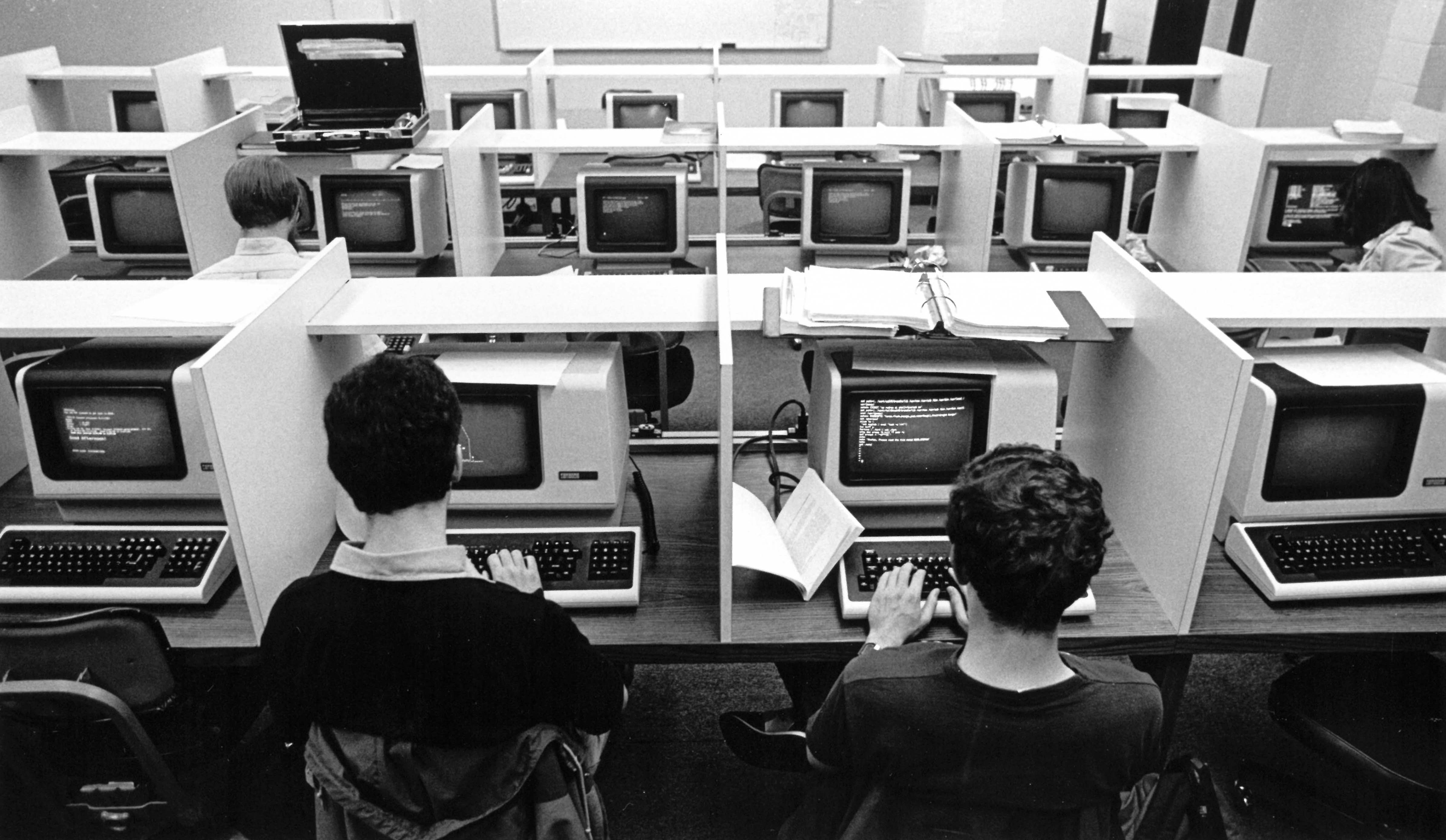

Students type away in the computer science lab of the Armerding Science Building.

1985

Students seated in the Todd M. Beamer Student Center plug smartphones into communal chargers and scroll through social media while waiting for their friends to arrive. Electric scooters take students from Billy Graham Hall to Fischer Hall on the other side of campus in under a minute. Musicians plug their instruments into amplifiers while the sound technician adjusts the A/V setup in the back of Edman Chapel. Laptop screens light up classrooms.

Technology is woven into daily life on Wheaton’s campus. But it hasn’t always looked like this. So how did we get here? And where is technology headed next?

When Jonathan Blanchard founded Wheaton College in 1860, the passenger elevator had recently been unveiled in New York and the telegraph was considered relatively new technology. The world was still eight years away from the first typewriter and 16 years away from the first telephone.

Although those earliest generations are gone, archival remnants paint a picture of the ongoing advance of digital technology at the College. Former students and professors can tell the tales of the first time they touched a keyboard, used a digital printer, and connected to the world wide web. These days, students experience an entirely new wave of technology as innovation takes our devices to ever-expanding levels.

MAJOR TURNING POINTS

There were a few technological advancements that unequivocally changed the way education—and the world—functioned. The telephone was just one. Invented in 1876, it had gained popularity and accessibility by the early 1900s.

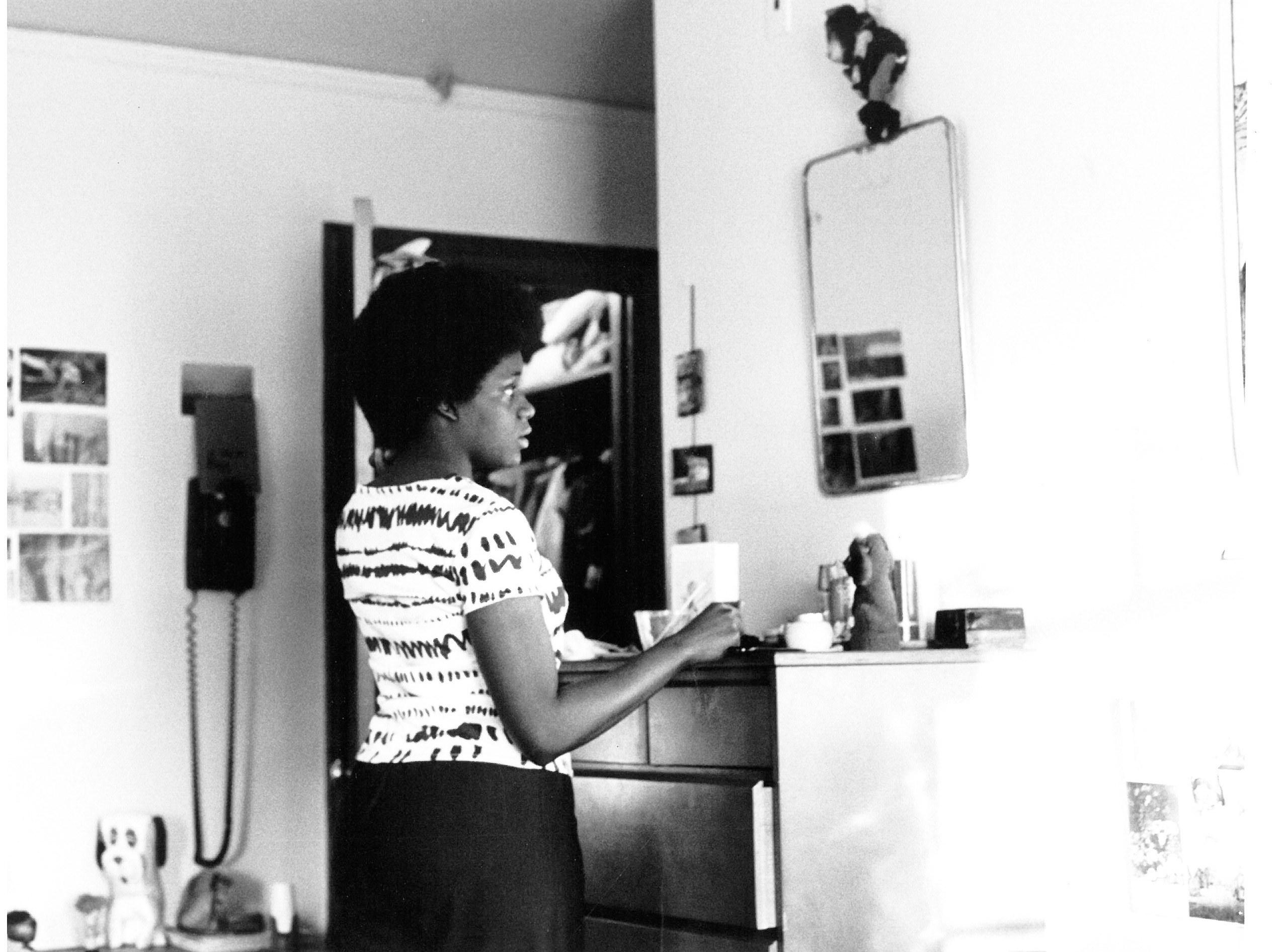

In 1940, the senior class gifted an inter-office telephone system to the College. In 1965, Ray Smith ’54, then president of the Wheaton Alumni Association, made the first touch-tone phone call. The call was to Billy Graham ’43. Eventually, phones were so common and integral to daily life that each dorm room had a corded telephone installed on the wall.

Carol Parks ’81 prepares for the day with a corded telephone visible in the background.

1980, photo by Anne Carter

One student, Stephanie Ault Justus ’93, remembers using a long cord so she could find privacy in the hall or in a suitemate’s room. She also remembers having to memorize a new number every time she changed rooms.

Then came cell phones. Fifty years ago, in 1973, the first cell phone call was made on what was referred to as “the Brick”—Motorola’s DynaTAC model. It had enough power to last for 30 minutes of conversation.

Cell phones became more widely used at the end of the ’90s and the early 2000s. The iPhone came out in 2007, ushering in a new era of mobile capabilities. Now, it’s impossible to walk across campus without seeing a smartphone held up to an ear, clutched in a hand, or tucked into a backpack or briefcase.

The first computers appeared at Wheaton in the late 1960s for programming classes. By the ’70s, computers were used for administrative tasks, and in the ’80s, personal computers began cropping up around campus. By the early 2000s, nearly everyone—faculty, students, and staff—had a personal computer.

Email was born in 1971 and arrived at Wheaton as early as 1983. In the beginning, it was largely faculty who used it, and mostly for communicating with other institutions. Conversations took days: Batches of emails went out every 3–4 hours by means of a connection to Bell Labs, Wheaton College’s dialup distribution hub.

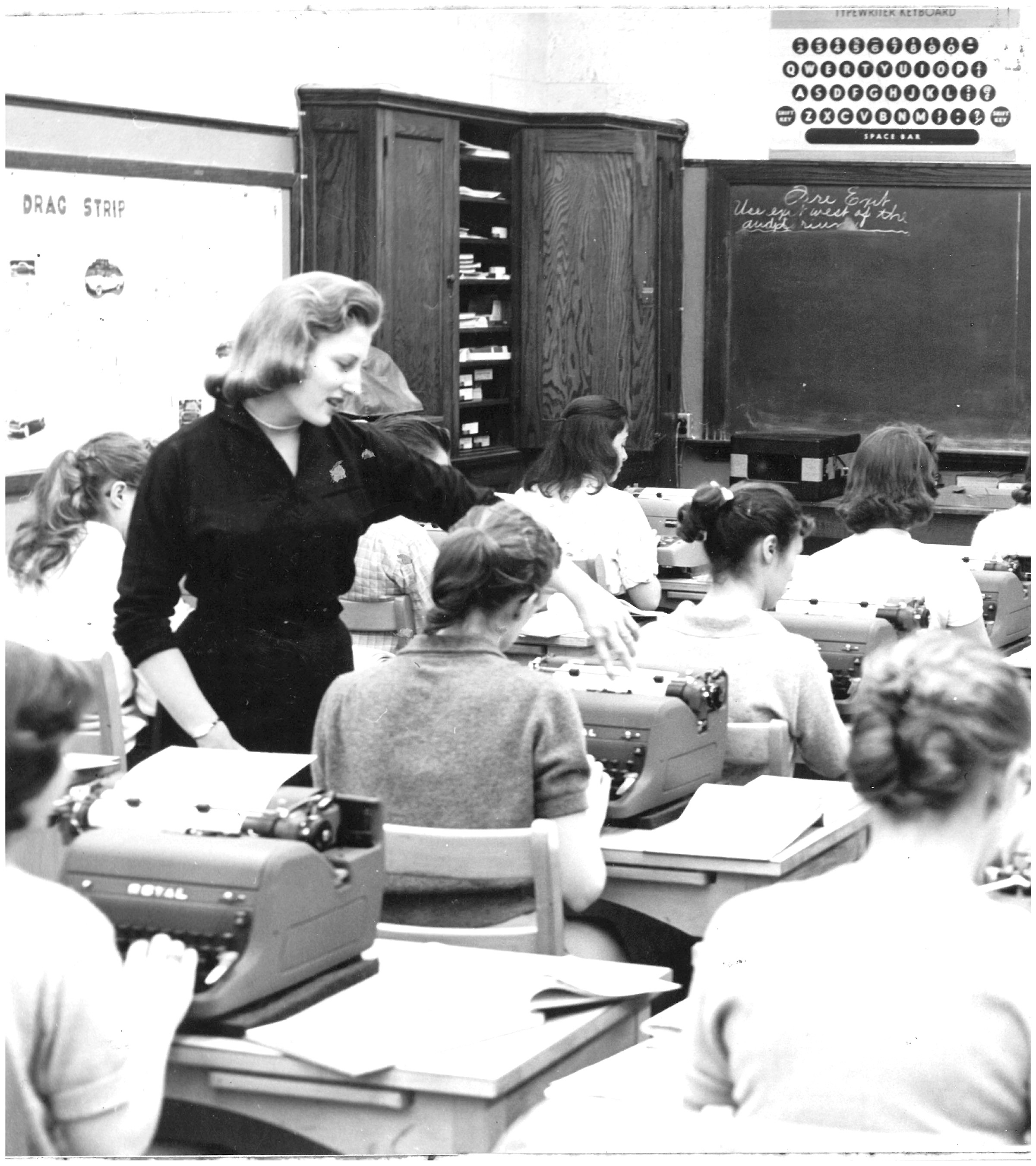

An instructor helps a student in a Wheaton typing class.

1957

Although email was available and accessible to anyone on campus, students were slower to adopt the technology initially. Because of Wheaton’s smaller size, they could easily talk to professors in person. Wandering down the hall to a professor’s office was sometimes just as convenient as sending an email.

As the internet became available to the public in the early 1990s, the Wheaton community at first accessed it using modems. Then, in the 1992–93 academic year, the College established Wheaton Online, the school’s first personal network. It functioned at 56 kilobytes per second, a speed that would take over two days to download a movie, that is, if the line stayed active. Today, Wheaton’s internet connection is 3.5 gigabits per second, millions of times faster.

Trying to quantify or qualify the impact of the internet is nearly impossible. From global connection to powerful search engines, the internet changed everything, especially for academia.

In 2015, to accommodate the ever-changing and ever-growing technological landscape, Wheaton hired Wendy Woodward, the first senior director of information technology and chief information officer at the College. Her role was to centralize all technology endeavors and ensure that the College could hone its focus and effectiveness in technological advancement and maintenance.

TECHNOLOGY IN THE CLASSROOM

Some pieces of technology, while seemingly mundane, have made a huge difference in day-to-day tasks for students and professors. Take the copy machine for example. Especially before laptops and digital materials, producing mass quantities of hard-copy articles, worksheets, and syllabi required copy machines and their many variations over the years. Dr. Lynn Cooper M.A. ’74, Professor of Communication Emerita, claims that to this day her right bicep is an inch bigger than her left, thanks to time spent cranking papers through the Gestetner and mimeograph machines.

“A lot of my engagement with technology was driven by the students. I ran to keep up with them,” Cooper said. “The College was always very generous in providing training for each new piece of technology that came, as well as good examples of how we could use it.”

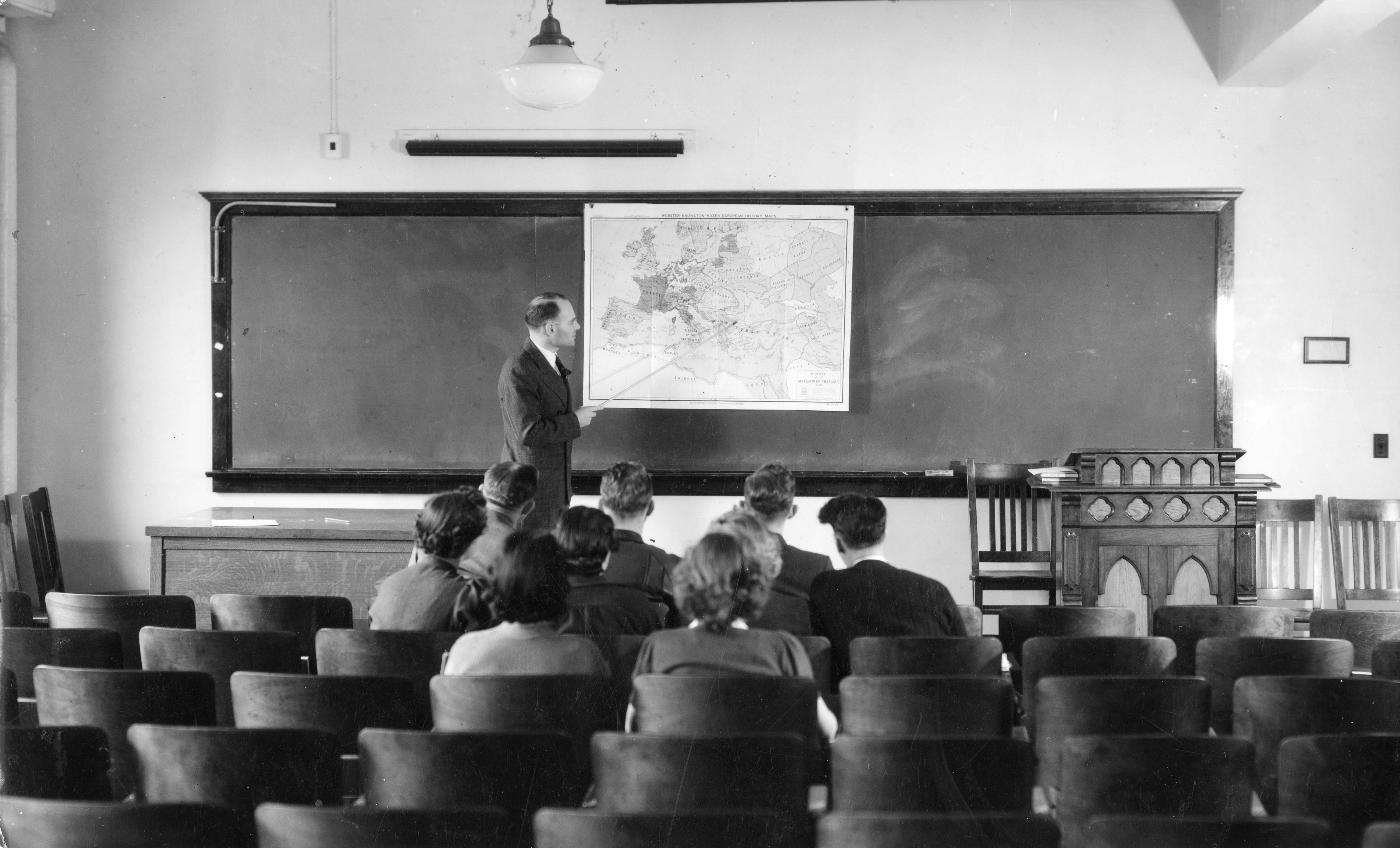

V. Raymond Edman, fourth president of Wheaton College, teaches a history class using a blackboard and map.

1935

For Cooper, one of technology’s most positive features was how it made standardization easier. In 2003, with the Instructional Technology, Computing, and Marketing Communication departments, Cooper created a standard grading rubric for speech classes to use. While students gave their speeches, professors filled out the digital rubric. Once the speech was over, the professor pressed send, speeding the rubric to the student’s email inbox, and giving students nearly instantaneous feedback.

Cooper also built an online speech center, which housed video samples of good and poor speeches and gave students a common standard to reference. The online speech center model garnered accolades: It received an award, was published in several papers and textbooks, and became a model for other campuses.

Dr. David Maas ’62, Professor of History Emeritus, was a proponent for the incorporation of visual aids when teaching to allow students to visualize historical events during lectures. “I tried to bring visuals as much as I could into the classroom,” he said. “I’m a visual learner, probably like most people.”

Incorporating visuals into lectures took some effort. At one point during Maas’ career, the school only had three overhead projectors, which had to be reserved in advance. To show a movie, the school used 16-millimeter film. “You’d have to get into the class early and run the movie to the part you wanted to show the students,” Maas said.

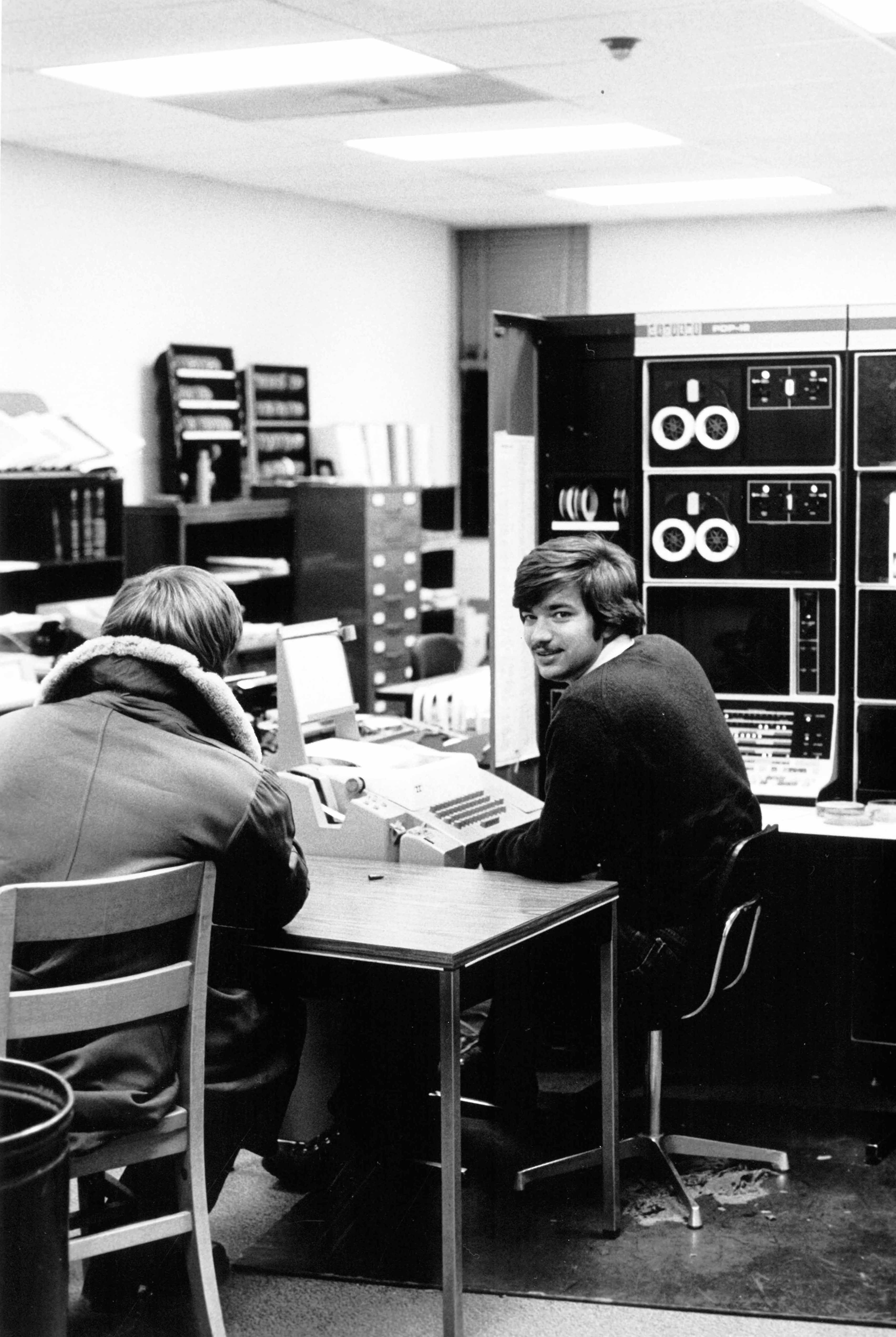

Two students chat in the computer lab.

1975

Not only did Maas use photographs to assist his students in learning, but he also used the visuals to help himself learn. At the beginning of each semester, he asked students to write their names on a piece of paper, then hold them up under their chin while he snapped a photo (Yes, like a mugshot). He then developed the film and studied each image to help him memorize their names quickly. Other professors caught wind of this idea and adopted it. Today, it is not uncommon for digital attendance sheets to include students’ school ID photographs.

Maas was also an early proponent for adopting computers on campus. In collaboration with Dr. John Hayward ’71, Associate Professor of Computer Science Emeritus, Maas wrote up a manual outlining the benefits of computers for personal research and teaching. Maas eventually bought himself one of the first portable computers—an early iteration of the laptop—the Osborne 1.

As a chemistry major in the early ’90s, Stephanie Ault Justus used computers for graphing data points. However, she and her classmates had to do most calculations by hand, and without Google or online catalogs, they used reference books to look up chemicals.

One of her favorite classes was Analytical Chemistry. In class, students tested molecules to determine each one’s composition. Molecular composition describes the atomic makeup of molecules. For example, a water molecule is made up of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom connected by chemical bonds.

When her daughter, Anastasia Justus Grotelueschen ’22, committed to studying chemistry at Wheaton, Grotelueschen was excited at the prospect of learning analytical chemistry and following in her mom’s footsteps. “Since I really liked it, she figured she might enjoy it, too,” Justus explained. “But it’s so different now; it’s all computer-generated. It was a disappointment to her because it was so different from what I described.”

Yet the growth of the sciences at Wheaton has resulted in many profound technological additions. In 1890, for instance, Wheaton College purchased its first telescope, fondly nicknamed “the Lemon” for its bright color and spherical shape. Faculty, students, and community visitors used the observatory, located on Blanchard lawn. Some wonder whether Edwin Hubble, who was raised in Wheaton, IL, visited the Lemon and gained early inspiration. The Lemon was moved to the HoneyRock Center for Leadership Development in 1972.

Meyer Science Center, the College’s state-of-the-art science building completed in 2010, holds a wealth of valuable and powerful pieces of technology, from geological modeling software in the basement, all the way up to the PlaneWave Instruments CDK24 telescope in the rooftop observatory.

THE STATE OF TECHNOLOGY TODAY

As headlines continue to suggest, advancements in technology are not slowing down. The recent explosion of artificial intelligence (AI) is just one area in which technology continues to expand and impact daily life.

Camden Flannagan ’26, a computer science major, occasionally uses ChatGPT, an AI-powered language model that has generated significant public attention. He explained that it is useful for getting started on projects, like generating a speech format or writing boilerplate code. Although he recognizes the usefulness and power of AI, he does not anticipate that it will fully replace human influence when it comes to coding.

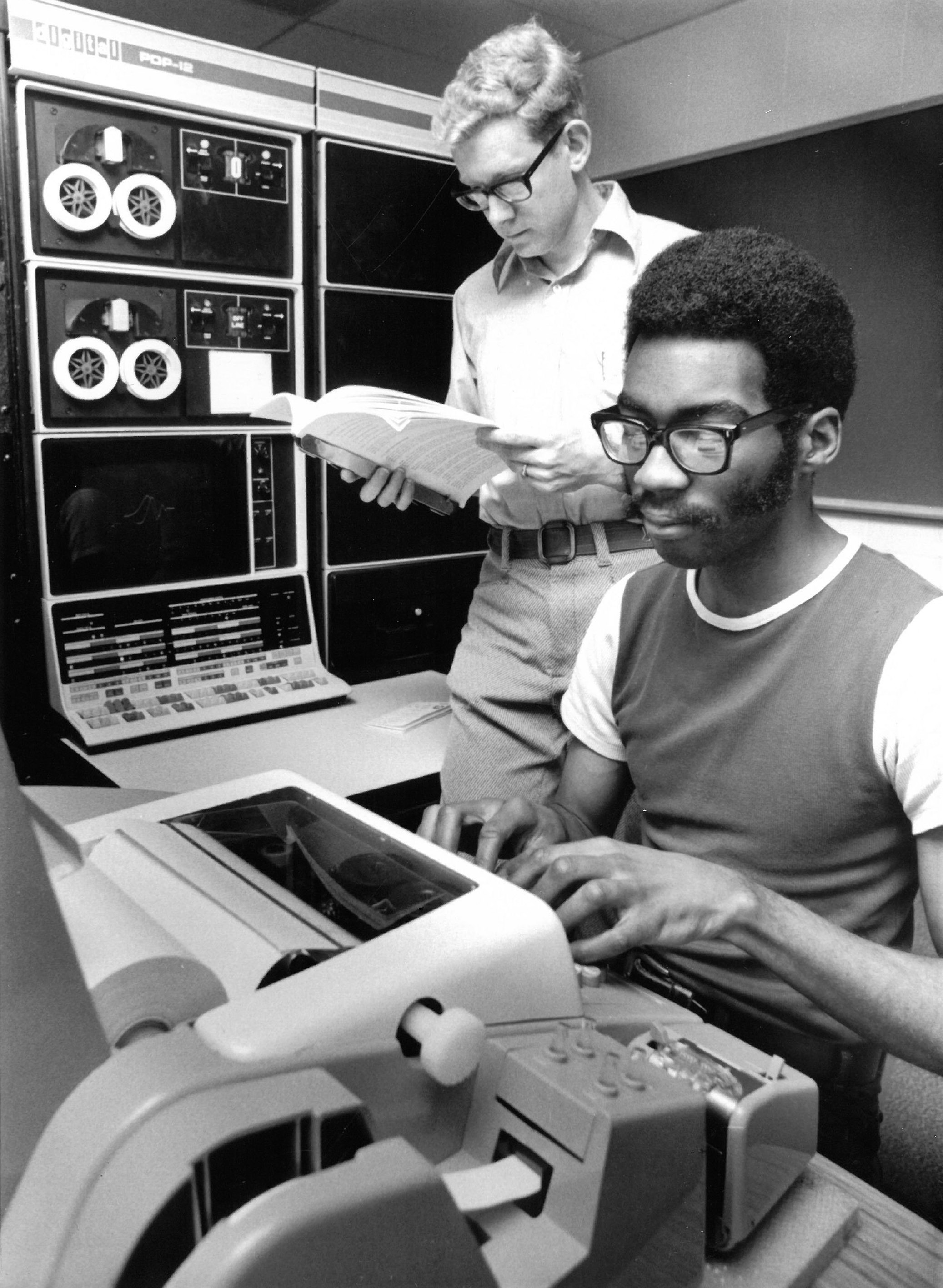

Two students work in the computer lab.

Early 1970s

“As a computer science lover, ChatGPT both terrifies me and brings me so much joy to see it working,” Flannagan said. “On the one hand, it’s amazing, but on the other hand, it needs to stay in its place.”

Outside of coding, Flannagan’s other passion is music. He creates electronic music and publishes it on YouTube, a collision of software and social media that would have been unheard of just two decades ago.

“I love classical music,” Flannagan said. “I hear musicians doing these amazing things with their hands that I can’t. My computer gets me a bit closer to making those sounds. It’s amazing to me that I get to do that, even though I can’t actually play the piano all that well.”

In the same way that the internet connected people to information, resources, and people that they might have never known before, technology has continued to pave paths for people to achieve in areas that might have been otherwise inaccessible.

When looking back at the past decades of technology at Wheaton, Cooper reflected, “There has been quite a bit of change, but all to the advantage of students.”