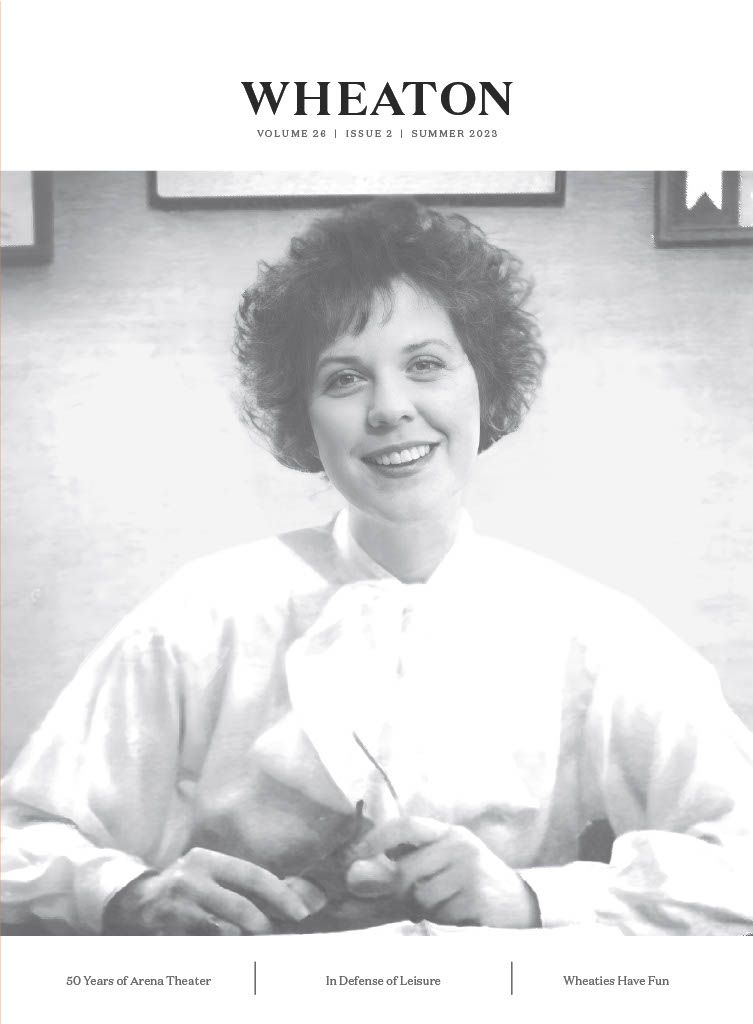

50 Years of Arena Theater

A Celebration of the Program That Brought Over 100 Stories to the Stage

Words: Cassidy Keenan ’21

Photos: Casper Carter, Buswell Library Archives & Special Collections, Tower Yearbooks

Secret in the Wings

2007

Once, I sat in an acting class as a member of Arena Theater. A classmate stood before us, getting ready to present her project. She told us she was scared to perform because she was scared she wouldn’t be enough. We all hummed and nodded and took several deep breaths, as was our custom. Our professor and director, Mark Lewis, leaned forward in his seat and answered kindly, “Okay, what if you’re not? What would it be like to accept the fact that you’re not enough, to give yourself permission to not be enough? And then to do it anyway?”

Arena Theater is many things. Over the last 50 years, Arena has been a performance space, a classroom, a sanctuary, and a refuge. Plays have come to life on chapel stages, in houses, basements, and small black box theaters, in the old gymnasium of a refurbished elementary school, in parks and courtyards. Fifty classes of students have come and gone. Professors, directors, beloved faculty members, and college presidents have entered the Wheaton College stage, performed their roles, and then exited. Through it all, the theater has remained constant: deeply and indescribably cherished, passed down with breathtakingly gentle hands from each generation to the next.

Defining Arena is an impossible task, and I am not up to it.

So I will simply tell a story. That’s what I think Arena is at its core, and it is the place where I learned to tell stories, after all. It is a story of community and love, of people coming together to be bodily present in a room and to see each other. It is a story of curiosity, hope, fighting cynicism, and encountering Christ. The story includes twists and turns, lines and shapes and colors, observing how the structure of the environment around us shapes our perception of the world. The story has heroes and heroines, all of whom came together, however briefly, to be part of something bigger than themselves. The story is fragile, no single chapter of it has ever been guaranteed, and no one yet knows how it might eventually end. But it has continued on for a full 50 years, and that is remarkable. It is an impossible task. I am not enough for it. Let’s do it anyway.

The Crucible

1973

ALTHOUGH WE ARE celebrating the 50-year anniversary of Arena, it is important to note that theater existed at Wheaton College longer than that.

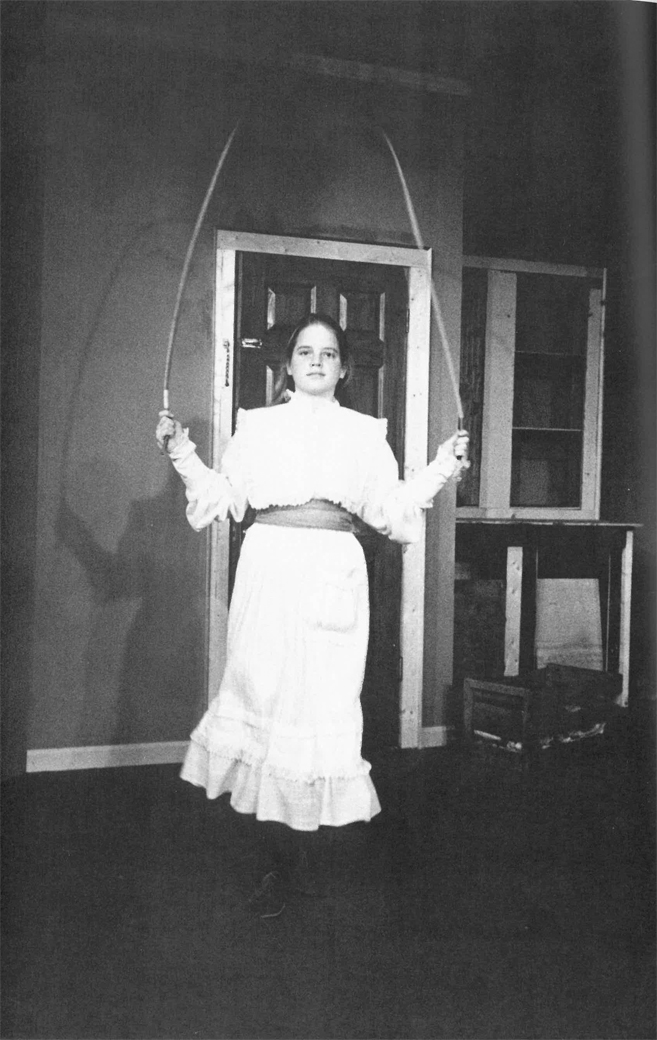

The true beginning of our story dates back to the 1960s, following earlier rebuffs from College administration. For example, President Raymond Edman prohibited theater on campus throughout his tenure on account of what he deemed theater’s “worldliness” and the “unsavory” nature of the acting profession, as he wrote in a 1955 statement to the Record. Once drama was officially authorized as a creative art at the College in 1965 under President Hudson Armerding’s leadership, theater took root and bloomed in unexpected nooks and crannies of campus. Performances were staged in Plumb Studios, which is now the basement of Buswell Library, and in Edman Memorial Chapel. Grainy, black-and-white photos of costumed students dramatically silhouetted against the chapel stage began appearing in the pages of the Wheaton yearbooks.

Theater was enthusiastic but still new, with no dedicated performance space and scant supporters.

Enter Jim Young.

Jim Young is perhaps the first great hero of our story, arriving on campus as a visiting professor in 1972. By the end of that year, he had cleared out the storage area in the basement of Fischer Hall as a theater space, established a company of just over 30 students to form a core ensemble, and begun rehearsals for a production of The Crucible. Here, in the fall of 1973, is where “Nystrom” Arena Theater was truly born, named after Dr. Clarence Nystrom, a former communication professor at Wheaton.

Students gathered with varying degrees of wariness for the first meetings of “Workout,” a theatrical company inspired by the lower-east-side ensemble structures in 1960s New York. Workout: a name that had appeared to Young in a burst of inspiration like it was written in the sky. It’s a holy name, based on the charge offered in Philippians 2:12 (NIV) to “work out your salvation with fear and trembling.” Gary Sloan ’74 was a student among this brave new class of pioneers who found themselves standing in Arena Theater in the fall of 1973—a low, long, dusty, windowless, concrete storage space in the basement of a student dormitory.

In this most unlikely of places, our thespians created indescribable magic. Under the watchful and ever-enthusiastic eye of Young, 30 to 35 students gathered to experience the world of theater in a way they had never known. They learned about Beckett and Shakespeare. They watched films by great directors like Ingmar Bergman, with performances by great actors like Marlon Brando. And they met in the basement twice a week for the very first company rehearsals of Workout.

The weekly Workout meetings are perhaps the hardest aspect of Arena to describe. This is partly because of one of the very few concrete rules of Workout: There are no observers. Everyone in the room must be a participant, though anyone has absolute freedom to say no to any game or exercise at any time (another rare rule). It is hard to explain to someone who has not experienced it personally. This part of the story is better lived than told.

A technical description of Workout might read something like this: The company of students gathers twice a week, and they play games or exercises to explore their physicality, imagination, and emotion, getting in tune with themselves and each other.

However, the reality of Workout is infinitely more tender, spiritual, and complex. In it, for 50 years, students have done all manner of nonsensical things. They have stood face-to-face with each other, forming “mirrors,” and spent five minutes mimicking each other’s motions exactly, learning how to observe and honor each other. They have raced around the room, freezing in various poses in games of “moving statues.” They have returned to childhood, singing old songs, playing pretend, building castles, and hatching dragon eggs. They have thrown “nets” or “stones” together in order to cast off trauma and fear. They have told stories in five sentences, repeated important words that other people have offered them in the past, or even just sat in the room and cried.

The key to all of this is that no one is doing it alone. Whatever game they play becomes the work of the ensemble. The rest of the company listens to the stories being told, repeats the words back to the speaker, or comes alongside the crier, holding them tight. Students witness, accompany, and sometimes even lovingly oppose each other.

Stories are told, and they are told together.

The Rope Dancers

1982

ALTHOUGH SO MANY of the people who knew him speak of him with reverence, humor, love, and awe, Jim Young proves almost as difficult to define as Arena itself. Sloan described him as “a man full of prayer and insults.” Randy Petersen ’78 spoke of his enormously deep and genuine heart, the singular care he had for every person he encountered. He also emphasized how Young loved and challenged his students in equal measure, encouraging them even to break tradition: “He was postmodern before postmodernism was cool.” Jane Cook Tawel ’81 recounted how Young came up with a specific and unique nickname for each person in Workout.

I’ve heard so many stories about Young, told through laughter and through tears. Once, Sloan finished performing a scene for a class and looked to Young for commentary, only for the professor to slam his clipboard down and yell, “You are so frustrating because sometimes you can be so good!” In the ’80s, Tawel starred in a production of The Diary of Anne Frank. To prepare her for the role, Young got approval for two actors playing the guards to bang on her dormitory door unexpectedly in the middle of the night and march her across campus. Young, people agree, was not always easy.

But more than anything else, Young emulated and embodied Jesus’ love. He cared for each student with an unwavering passion and invited them to encounter Christ time and time again. He loved the bodily presence of theater because it mirrors the incarnation of Christ. He began one of the most cherished theater traditions that has continued to this day: At the beginning of each year, every class of Workout placed their hands on the walls of the Fischer basement and prayed into the space.

I don’t have words for this type of legacy, but I invite you to consider what it must be like—to enter Arena, to touch the walls, and to know that nearly 50 years of prayer uphold you.

ANOTHER VITAL CHARACTER comes in the form of Michael Stauffer ’70. First an enthusiastic theater student, he later joined the faculty of Wheaton as a speech professor in 1979. In doing so, he became one of the pillars of Arena. This is a key turning point in our story because the theater staff at Wheaton had undergone a monumental change, expanding from one person to two. Stauffer’s is another legacy that cannot be understated. He provided an entirely new and essential component to theater by introducing Wheaton students to the world of stage design.

No longer did Arena take an exclusively Peter Brooksesque approach to theater, nothing but an actor walking across an empty stage in front of an audience. Stauffer brought ideas about costumes, set, lighting, and props. He encouraged actors in Workout to explore color, lines, geographical space, and how to enrich the story just by crafting a specific kind of world on the stage. One only has to consider his 2011 production of The Odyssey, where he filled the entire stage with gallons of sand to bring a real-life deserted island straight to his audience, or his 2019 production of Peter and the Starcatcher, where he incorporated everything from puppets to sword fights to giant moving sailboats to actors literally lifting each other off the ground and “flying.” Stauffer eventually became a theater professor, director, and stage designer at Wheaton, helping students learn many valuable lessons. Theater is more than just entertainment, theater is more than just acting, and most of all, theater requires attention and engagement from artists and audience members alike.

OUR STORY HAS not been without conflict. From the very beginning, Young, Stauffer, the students of Arena, and so many others fought to keep the theater alive. There were many moments of tension as they grappled with a lack of space, resources, and funding. To make ends meet, Young’s and Stauffer’s wives stepped up to manage the box office as volunteers. Young supplemented whatever the College could afford for productions with money out of his own pocket. Stauffer once spent 372 hours working on a single production to ensure that the play was successful. Both professors regularly swept and cleaned the theater themselves in the absence of custodial staff.

Even amid opposition, the theater continued to grow. Practices became traditions, and each generation of Workout—especially seniors—taught the patterns and games to the students who came after them, handing the theater down through the years. A shared culture, a common language, and a generational legacy were beginning to form.

Furthermore, there were principal moments of triumph alongside the conflict, such as the acquisition of a new performance space in the early ’80s. Clifford Elementary School went up for sale. Through an enormous amount of prayer, a generous bid from the Wheaton College administration, and nothing short of a miracle from God, the property became part of Wheaton’s campus. That building is now known as Jenks Hall, the home of Arena for nearly four decades.

After the first spring play performed in Jenks Hall, Jim Young invited back every graduate of Workout since 1973. At least 30 to 40 alumni formed a processional from Fischer Hall to Jenks, lifting the generations of prayers out of the old walls and carrying them together all the way across campus to place them in the walls of the new space.

Julius Caesar

2022

THE ARRIVAL OF one Mark Lewis in the winter of 1994 marked a new chapter to the story. After serving as a guest director for a play that season, Lewis officially joined the staff as a director at Arena and as Young’s replacement as director of Workout. Although he did not feel himself to be the likeliest choice, having never attended Wheaton or been a part of Workout himself, Lewis’ chapter of the story has been every bit as meaningful in new and unexpected ways.

Lewis did not send students to drag each other out of bed in the middle of the night for the sake of a show, but he began to impress upon students the weight and value of their own individual stories. In the new Workout rehearsal room in Jenks Hall, dubbed “Setzuan,” students walked back and forth in the light from the enormous windows as Lewis guided them to wrestle with unbelief and practice radical empathy. They walked through doorways and stood wordlessly in front of their entire company, leaving themselves vulnerable to be “reconsidered.” Lewis encouraged students to learn how to receive one another, to hold each other’s stories well, to linger longer in moments when the speedy pace of life encourages us to rush. Workout was entirely new—and entirely the same in the ways that mattered.

Jenn Miller Cribbs ’99 and Felicia Bertch ’02 were part of Mark’s first class. Both of them have expressed the intense atmosphere of spirituality, permission, and acceptance they received in the space. Cribbs learned that the work of both actors and Christians does not happen from a solely intellectual place and that it is possible to stand before God completely as you are, no strings attached. “God does not love you in spite of anything,” she explained, “but in the midst of it.” Bertch found purpose and community at Arena, learning to value relationships and people over product. She reminisced on the joy of re-entering childlike spaces, allowing herself to play and be curious about things.

Naphtali Fields ’10 emphasized the way Arena served as a counternarrative to her life before college. Through strange and sometimes inexplicable acting exercises, such as standing before her entire acting class with an enormous wooden anchor to represent her life on a fishing boat in Alaska, Fields found magic and possibility. She found the ability to reveal something about herself and to extend an invitation for others to respond.

Another member of Lewis’ first class was Andy Mangin ’99, who eventually joined Arena staff as its first official technical director. This also marked the development of “crews,” one of the most important and communal experiences at Arena. It is tradition for every member of Workout to belong to a stage crew for each show, whether it is building sets, sewing costumes, hanging lights, or gathering props. This service model of theater is unique and immeasurably priceless—not to mention extremely bonding. Some of the closest relationships in all of Arena might have been forged while making hundreds and hundreds of frantic, tiny stitches for the perfect Victorian-era Pride and Prejudice dress, with opening night looming closer by the minute.

AND SO, AFTER all this, we find that the story continues. Arena was and is a space of community the likes of which many of its members had never experienced before. Stauffer began teaching more classes, such as Theater Survey, Scenography, Directing, and Church and Theater, offering students a well-rounded theatrical experience. Mangin became a full-time director in addition to his professorship and technical position, forming a third pillar of Arena between Stauffer and Lewis. Season after season of heartfelt, challenging, thought-provoking plays came to the stage and left again.

New traditions and Workout games blossomed. Students lifted one another to the Lord. They created special ceremonies to welcome new members to Workout and to say goodbye to graduating seniors. They regularly ate together, singing a prayer of thanks hand in hand before every meal. They exchanged heartfelt, handmade, specific gifts in a ridiculously elaborate game of Secret Santa each Christmas. At the close of each show, the members of Arena spent all night disassembling the set together, cleaning the theater, and preparing the space for its next adventure, always and without fail sharing a meal together afterward. Arena expanded even further by adding different programs, such as trips to the Black Hills and Shakespeare in the Park, which attracts thousands of Wheaton-area community members each year. Alumni from all years of Workout still return to teach and perform in the latter.

Middletown

2013

The story moves on through countless more chapters. Some are full of heartbreak and loss, like Young’s death in 2012. Some are overwhelmingly, inexpressibly, universally difficult, like the arrival of COVID-19. Yet even these had their own silver linings, such as the experiment of the first-ever virtual, multigenerational Workout, or the year Workout temporarily relocated to Pierce Chapel and everyone attempted to perform with masks, six feet apart. Some chapters were bittersweet, like Stauffer’s eventual retirement in 2022.

Through it all, through generations of members and actors and artists, Arena has remained. It is more than just the performances, more than the classes, more than Workout, even more than all the extremely unlikely people and the relationships themselves.

Somehow, in some way, and for 50 years now, Arena has become something greater than the sum of its parts.

ARENA THEATER IS impossible to describe. I have no ending to offer because the story continues. Never has that been clearer to me than as I prepared to write this article. When I spoke with Lewis, Stauffer, and Mangin for hours about the beauty and meaning of Arena. When countless alumni leaped at the chance to speak with me about it, so eager to share their stories, whether they’ve been graduated for a dozen years like Fields or almost 50 years like Sloan.

The last person I spoke to was Parker Ohman ’23. I concluded our interview by asking him what he wished more people knew about Arena. He paused, his eyes thoughtful.

“That it exists,” he said after a moment’s consideration, and we both laughed. “It grieves me to know that there are a lot of people who go through their Wheaton experience who would really benefit from the theater and don’t ever realize that it’s a possibility for them. It is not a perfect place. But whoever you are, whatever your background is, whatever your regrets and your joys, there is a place for you here.”

Arena exists. Not only does it exist, but it is also treasured. It is valuable. It is essential. It is an ongoing story, and we have no idea where the story will go from here.

But it has lasted 50 years now. And that is remarkable.